What’s an Avant-Garde Evening Without a Poet and Plush Toys?

Steve Smith in The New York Times

The poet Steve Dalachinsky is as consistent an indicator of a high-quality concert experience as any I have found during 20 years of concertgoing in New York. Surely, you reckon, he’s also seen some duff dates in his decades as a regular habitué of the city’s nightclubs, concert halls, lofts and provisional spaces. But I have trouble recalling any significant, edifying or exhilarating free-jazz or total-improvisation concert I’ve attended at which Mr. Dalachinsky has not been in the audience, rough-edged, congenial and ready with an opinion.

That notion held fast on Tuesday night, when the Issue Project Room in Downtown Brooklyn hosted the second concert of Ten Years Alive on the Infinite Plain, a festive 10th-anniversary series running through late October. The event brought together three important, idiosyncratic artists representing disciplines that Issue has helped nurture during its first decade.

Mr. Dalachinsky, reliably, was present. This time, though, he was a star attraction, starting a long evening that included sets by the saxophonist Joe McPhee and the pianist and performance artist Charlemagne Palestine.

A mixed bag for sure, but Mr. Dalachinsky drew connections in his opening remarks. He and Mr. McPhee, fellow travelers in the ecstatic-jazz scene, knew each other well, he said, adding that he and Mr. Palestine were more recent acquaintances but had bonded quickly as fellow Brooklyn Jews and misfits.

Offered in succession, Mr. Dalachinsky’s set and Mr. McPhee’s were complementary. Mr. Dalachinsky used a song — Robert Johnson’s “Come On in My Kitchen” — as a thread to seamlessly stitch together two of his poems, “Son of the Sun (After Magic)” and “Sweet & Low (Word of Light and Love/The Bill Has Been Paid).” Mr. McPhee used a poem — Langston Hughes’s “Birmingham Sunday” — as a motif to bind disparate patches of musical and textual terrain.

Mr. Dalachinsky, beholden to the Beats but seasoned by meaner times, recited with a jazz-horn flow. He rushed one phrase and elongated the next; occasionally he stuttered on a single syllable, and then released the pent-up tension in a gush. Mr. McPhee, on tenor saxophone, mustered a pastor’s incantatory tone to recall the September 1963 bombing of a black church in Birmingham, Ala. In an eruptive soliloquy partly based on Duke Ellington’s “Come Sunday” and partly on the hymn “Lift Every Voice and Sing,” he repeated the names of the four schoolgirl victims like a mantra.

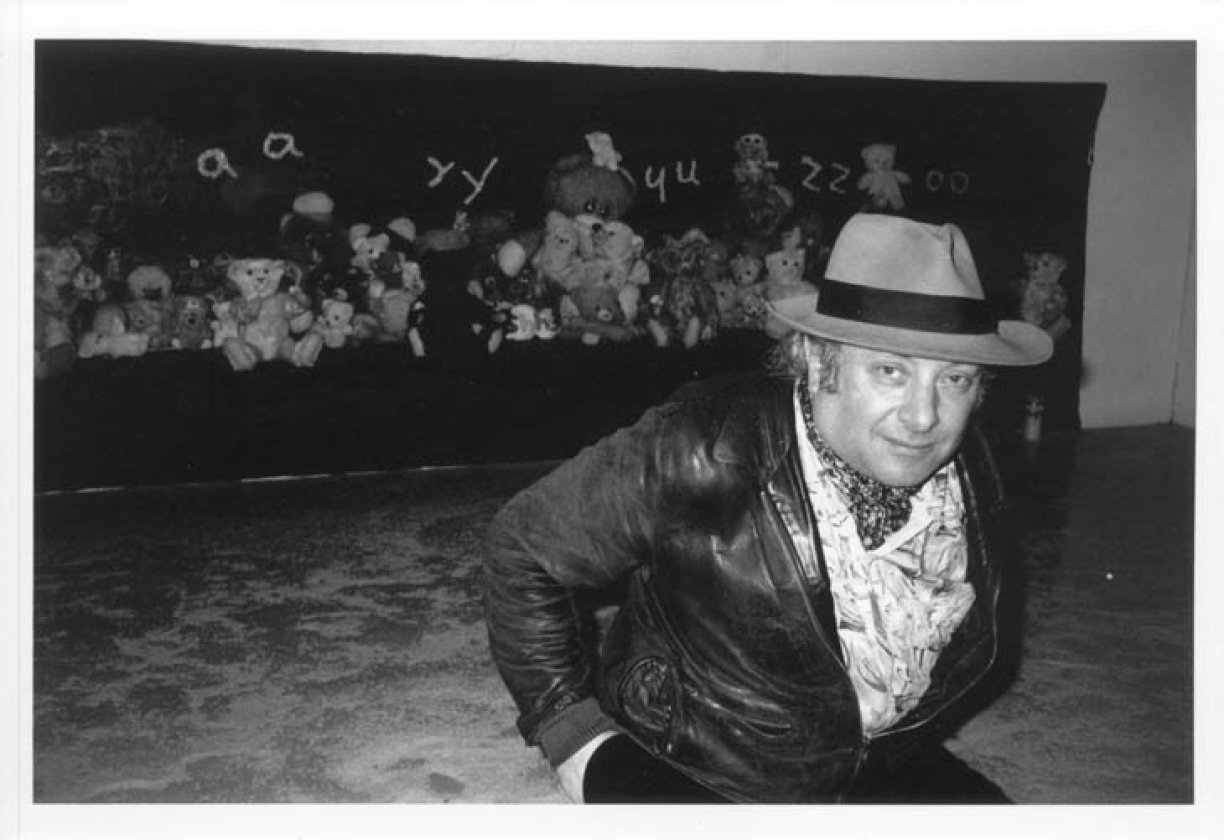

In the wake of Mr. McPhee’s wayward sermon, Mr. Palestine’s closing set felt like a healing ritual. With his customary menagerie of plush toys at hand, he paced the room, singing softly while rubbing a pealing tone on the rim of his cognac goblet.

After a quirky preamble played with polyphonic toys, Mr. Palestine finally sat at the luxurious Bösendorfer piano Issue had brought in for the occasion — his first Brooklyn performance since boyhood, he said. Sustain pedal pushed to the floor, he played two notes, then more, chords, then clusters, in constant alternation. Coaxing out the instrument’s hidden tones and voices with his rippling cascades, he built slowly and intently toward a final chromatic ascent. In its wake, he waved a hand assertively for silence, then gave his toys the final say.

A version of this review appeared in print on September 6, 2013, on page C10 of the New York edition with the headline: What’s an Avant-Garde Evening Without a Poet and Plush Toys?.

http://www.nytimes.com/2013/09/06/arts/music/steve-dalachinsky-and-char…

Photo: Charlemagne Palestine by Bradley Buehring