Visual artist Anthony McCall and guitarist and composer David Grubbs began working together in 2007 when McCall decided to tackle the issue of sound in his otherwise-silent, digital solid-light works. Their collaboration has heretofore resulted in recorded soundtracks for McCall's artworks, but "Leaving (With Four Half-Turns)" is their first joint effort involving live musical performance. This interview took place in McCall's Manhattan studio on June 21, 2012, not long after the first performance of "Leaving (With Four Half-Turns)" at Berlin's Sprüth Magers Gallery.

ISSUE Project Room: Leaving (With Four Half-Turns) is an example of what’s referred to as your “solid light” works. How would you describe these works to someone who has never previously experienced them?

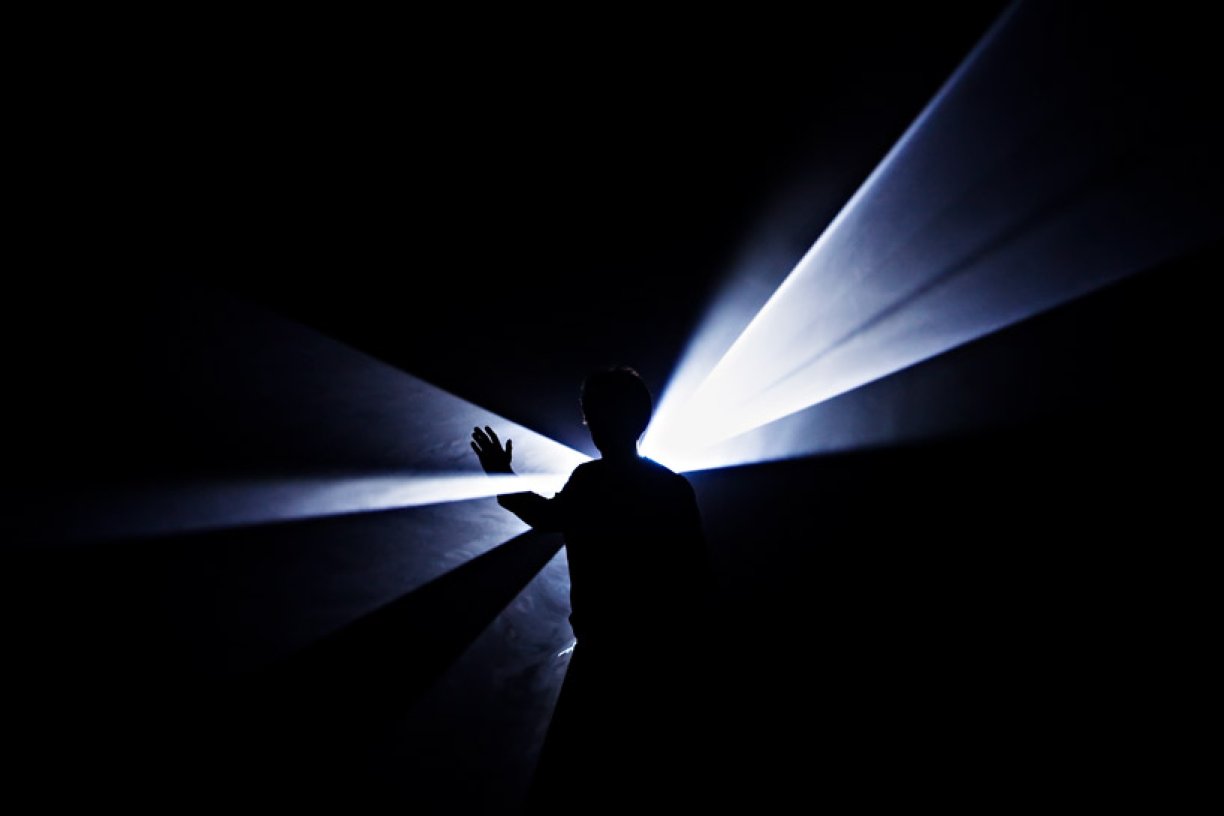

Anthony McCall: A solid-light film is one in which the projected beam of light itself is the primary focus of attention, rather than the image on the screen. Of course there is an image on the screen: a simple line-drawing. But when that line drawing is projected through a room filled with a fine mist, the beam of light that carries the drawing from projector to screen is revealed as a sculptural object in space.

IPR: What’s the genesis of the Leaving series, and how does Leaving (With Four Half-Turns) relate to this series?

AM: The first of the series was called Leaving (With Two-Minute Silence), which David and I worked on together on and off between 2007 and 2009.

David Grubbs: I have the sense of Leaving (With Two-Minute Silence) as being one particular solution to the question of sound in the Leaving series, and I think of Leaving (With Four Half-Turns) as a very different kind of solution. Many of the qualities that were present in our initial discussions about sound in the Leaving series were re-engaged with Leaving (With Four Half-Turns). Specifically I’m thinking about the idea of the role of sound with regard to a single, integral start-to-finish presentation of the work— unlike Leaving (With Two-Minute Silence), which is presented as an installation. There’s also the issue of using recognizable musical source material in what will be recognized as a musical composition.

AM: These are indeed significant differences. The fact that you are creating a musical composition rather than one made of ambient sound is one shift; and the fact that the composition will only be played once-through is the other: ‘listening’ in your piece requires a different order of concentration.

DG: I’m particularly pleased to be presenting this as a single performance, especially given that most of our conversations about the Leaving series have taken place while studying a diagram of the compositional structure of the work.

AM: What I liked about you taking Leaving (With Four Half-Turns) over was that from that moment on, it wasn’t necessary for me to know what you might do with it

DG: I took my cue from the visual materials. If you’re looking at the two-dimensional projection, Leaving (With Four Half-Turns) consists of three visual figures: a circle, a straight line, and a traveling sine wave. I roughly analogized those musically, as a starting point, as a repeated single-note figure, an open string that’s allowed to decay into silence, and a turnaround ornament. Just as the light becomes visible as a three-

dimensional sculptural volume through the medium of the haze, I begin the piece with an unamplified electric guitar, and by using a volume pedal an amplifier gradually becomes the medium for the sound of what would otherwise be a nearly inaudible acoustic sound source.

AM: Visually, there are four movements, and each movement consists of a full cone being gradually cut down until there’s nothing left. Each movement lasts seven-and-a-half-minutes, and each shares the same structure, but sculpturally speaking, each version is quite different from the other three. You maintain a very tight relationship to what happens in each of the four movements, but over the course of the four movements what

occurs musically begins to mutate. You began with the acoustic and by the end it’s highly amplified. Your musical composition requires concentration by the listener; and the volumetric form made of light requires its own, very different type of concentration. In some ways the senses one needs for each are in competition, and part of the pleasure is negotiating between the two. One particular comment from a viewer in Berlin stayed

with me: a friend told me that he of course knew that the film had preceded the musical composition, “but, as I stood inside the conical form observing and listening,” this friend said, “I had the strong sensation that the music was actually generating the sculpture of light.”

A full transcript of this conversation can be found on the Frieze blog: blog.frieze.com