Rock, Paper, Scissors, Guitar and Sound:

Keith Rowe With Graham Lambkin and Michael Pisaro at Temp

Ben Ratliff in the New York Times on AMPLIFY 2013: rotation, January 15th, 2013

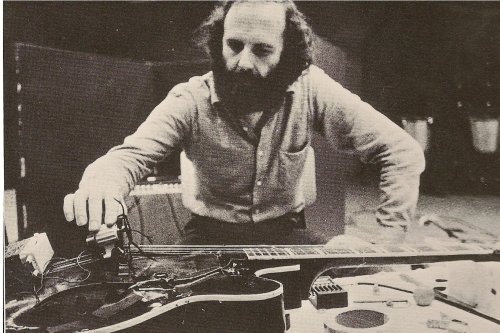

Keith Rowe is 72, and the instrument he’s been associated with for nearly 50 years is an electric guitar, laid flat on a table. Near the guitar are the things he uses for manipulating the sound of the guitar or interacting with it: flat objects of various weights and hardnesses, a couple of effects pedals, a small electric fan, a wad of steel wool, a small radio, an iPod, a sound mixer.

All of that lay before him on Tuesday night at Temp, the TriBeCa gallery space used for Amplify 2013: Rotation, a festival put on by Erstwhile Records and Issue Project Room. But he wasn’t touching any of it. He moved his hands across the surface of the table, creating hissing and rubbing sounds, supermagnified through sensitive contact microphones on the table. He was drawing, with pencil and paper. Beside him was another improviser, Graham Lambkin — a musician, writer, visual artist and former band member in the Shadow Ring. He sat at his own table, also drawing.

Mr. Rowe is part of a subset of improvisers who approach improvisation in nearly absolute philosophical terms. Starting in the mid-’60s, as part of the group AMM, he extended John Cage’s ideas about chance and nonintention in his own way. A Rosetta stone for the crew around Mr. Rowe was “Treatise,” by Cornelius Cardew, written between 1963 and 1967, a 193-page graphic score with few traditional symbols and no explicit suggestions of how to interpret it or what instruments to use. Mr. Rowe has been working with “Treatise” in one way or another for most of his life — even before it was completed, and ever since — and used some of it in the first half of Tuesday’s concert.

But Cardew’s bigger idea, that an improviser can build a language out of anything without relying on an established sound or idiom, was the night’s guiding principle. At his best, and the duet with Mr. Lambkin seemed pretty near that, Mr. Rowe constantly sets up and alters dynamic relationships among different sounds in a field, like a visual artist. He’s connected with his materials and uses fluid motions to keep the elements shifting, playing with your expectation and memory.

The performance was their first together. Mr. Rowe turned on the radio: salsa from a New York station. Mr. Lambkin drew lines along a ruler and traced circles around coins; he sliced across his paper with an X-Acto knife, making a sound much louder than the pencil. A blabby Geico commercial came on the radio, and as Mr. Rowe made small marks with his pencil — skrit skrit skrit — he triggered a recording of, appropriately, Pablo Casals playing the Bach cello suites. (Single lines in Bach, single lines on paper.) Mr. Rowe put his paper under the guitar strings and used them to guide his pencil hand; then he applied the steel wool to the strings, making an edgeless crumpling sound. Mr. Lambkin turned on a ghostly, barely audible cassette recording of Captain Beefheart’s “Well” and moved the cassette player around the microphones. Mr. Rowe made scissor cuts, loud and rude in their amplification, like pig snorts. Mr. Lambkin got into acrylic tape and plastic bags, ripping and sticking and scrunching, slow and deliberative and a little perverse.

It was a performance about motion and invention and constant reaction, and it had more spark than the earlier half: another first-meeting duet involving Mr. Rowe, with his usual setup — guitar, radio, etc. — and this time with Michael Pisaro, who is much more invested in composition with explicit instructions but also improvises with guitar, radio and recorded sound.

There were some parameters. They had established a length: 49 minutes. Mr. Rowe had superimposed six pages of “Treatise” as a prompt for his improvising, and on top of that laid a panel with a small square cut in the middle — an aperture, which he moved around as he needed. He sounded as normative as he can be, at ease in his own language. Mr. Pisaro, though he introduced unfamiliar sounds (tapping stones together, playing a field recording of cars along a rural road), ended up playing a long string of guitar notes, intervals and chords that sounded dry, mellow, theoretical and, finally, a little inert.

A version of this review appeared in print on January 18, 2013, on page C17 of the New York edition with the headline: Rock, Paper, Scissors, Guitar and Sound.

http://www.nytimes.com/2013/01/18/arts/music/keith-rowe-with-graham-lam…