Andrew McIntosh

Russell Greenberg: What are / were some of the inspirations for this new piece?

Andrew McIntosh: Lately I have been working on either extremely large-scale or very small pieces. Most recently I finished two 45+ minute pieces, a chamber orchestra piece, and several very small works, but nothing in the middle. I've been having a craving to work on a more normally-lengthed piece for around four or so instruments, so this opportunity came along at exactly the right moment.

Also, I haven't written too much for percussion or for piano, but earlier this year the chamber orchestra piece that I wrote had a huge percussion part and one of the large pieces mentioned above was for two microtonal pianos. Working on those pieces generated a lot of ideas that didn't always have an outlet at the time and that sort of "left-over" material is what is providing the foundation of the project for Yarn/Wire. It's sort of like I'm cooking the Yarn/Wire piece in delicious broth made from the remains of other recent pieces. I think this is a fairly common and also very logical method of working for anyone in the creative arts, so there isn't anything too exceptional about that, really.

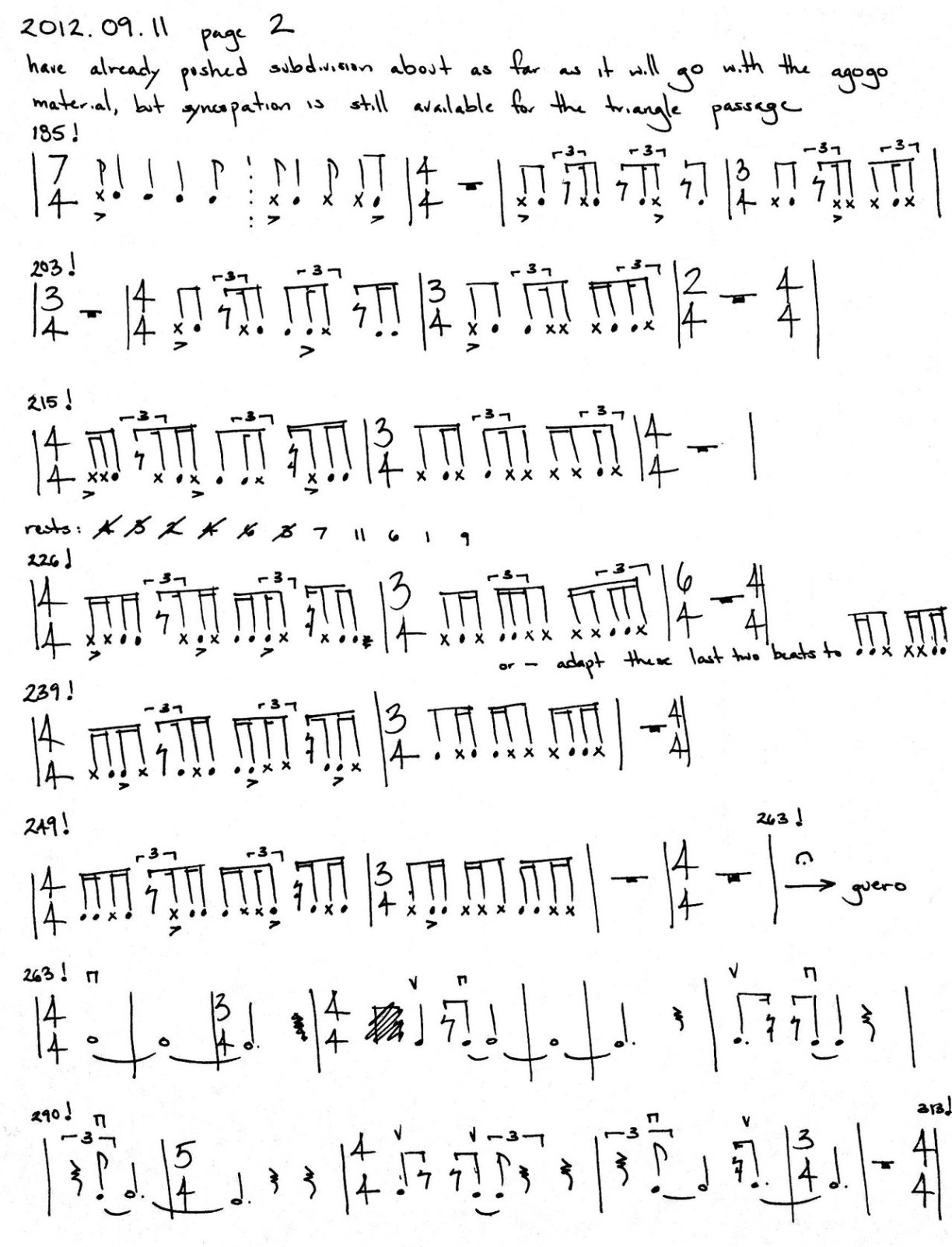

I guess the most direct way to answer your question is that the inspiration for this piece is coming primarily from a desire to further develop and explore ideas that I was working on earlier this year, since they seemed to imply other possibilities and directions than were relevant to their context at the time. What are these ideas, you might ask? Intuition versus form, rhythmical processes found in nature, creating unified or contrapuntal webs of sound out of multiple like instruments, juxtaposing sustained and/or microtonally just sounds with decaying and/or tempered sounds.

RG: Can you describe your process in writing this new piece?

AM: Over the past few years I've been exploring a rather architectural style of writing, where I start the project with a sound image in my mind and then start to construct a labyrinth of charts, shapes, and equations to manipulate and transform the structure in a sort of geometrical development. I love the elegant and evocative forms that can emerge out of perfectly constructed realizations of natural principles, such as symmetry, acceleration, relativity, periodicity, logarithmic curves, waves, etc.

This new piece definitely has some of that, but only in small pieces. Overall it is put together in a much more intuitive way. I am relying more on my instinct for this, asking myself questions like "what would I like to be listening to from these musicians?", "how long would I like to listen to it?", "what would happen if I took this other thing over here and layered it on top of what I just wrote?", "where does this sound want to go?", "what if this logical thing happens in the wrong order?", etc.

RG: What did you find particularly (intriguing, challenging, difficult, inspiring) about writing for our group in particular?

AM: Most of the music that I write is in just intonation, but re-tuning instruments is not an option with this instrumentation, so writing for pianos and traditionally pitched percussion is a welcome challenge. It is pushing me into slightly new territory and expanding my concept of how my harmonic language can function. I am finding that the focus that I often invest in microtonal harmony is now being directed towards an increased attention to timbre, balance (or lack thereof), and instrumental color.

Also, I have written quite a lot for sustaining instruments (strings, clarinets, etc.) and it is a joy to be working with these instruments where the sound generally only goes one direction. I'm reminded of Feldman's remark that the sound of a piano is "always leaving us". I am always interested in music that has a restraint or a limitation of some kind, and most percussion and keyboard instruments are restrained by the unavoidable decay of notes. Perhaps one could call it a morbid interest. I am always fascinated with the various ways that music parallels broader concepts in the natural world and with this instrumentation the individual sounds are constantly dying and being reborn.

RG: What made you agree to write for the group?

AM: I have known of Yarn/Wire for some time and colleagues of mine whose opinions I quite respect have spoken very highly of them, although I've never seen them perform in person. As a matter of fact, we almost met in person last year at the Unruly Music festival in Milwaukee, but our performances were on opposite ends of the festival and we missed each other by a matter of hours. Naturally, I was delighted when out of the blue I got an email from them asking me to write for them! Also, I knew that the instrumentation would provide an intriguing problem for me and would give me the chance to explore things that were already on my mind. Additionally, although we haven't worked together yet, they seem like thoughtful and fun people to work with and that is always a large factor in my decision making.

RG: What do you hope people will come away with after hearing this piece?

AM: This is a hard question for me to deal with. In the end I generally choose to ignore it until after I am done writing a piece. I find that it is very difficult for me to have thoughts about what an audience will take away from (or give back to) a piece in the process of creating it and still retain an honesty and integrity in the work. For instance: risk, fragility, and physicality are all very important to me as a musician and those things can be frightening to bring into the world as an artist. If I worry too much about how a piece that is fragile, imperfect, or provocative will be received by an audience then I will be tempted to temper the risky element and then I will have created something that is both disingenuous and also not as compelling as it could be. Since I am still in the middle of writing this piece, I cannot take an objective look at it yet to assess what I hope its affect will be. Perhaps its a bit like Dr. Frankenstein laboring over his scientific work and then having to deal with the consequences once the monster has come to life.

Also, (and this is a centuries-old concept among artists), I feel often like I am not necessarily "creating" things, but rather that the compositions have a life and a journey of their own and I am simply bringing them to light. In that case it is necessary simply to follow the path that the work needs to take rather than to create its path. Thus, in a way, I almost find that it is odd to take responsibility for the creation once it is complete, since it usually feels like something I discovered rather than invented. While I of course want people to be profoundly and positively affected by the music I write it is not really my job to create music for that purpose.

It sounds a little harsh to put it this way, but in the end what people take from a work of art is their own business and it will depend completely on who they are, the context in which they encountered the art, their own experiences, and an infinitely complex mix of factors outside of the art itself. For a direct answer: I hope that what people take from my music will be as complex and varied as the humans who encounter it.

That being said, there have been a few pieces I've written where, once I followed them to their natural completion, I decided that I didn't want to bring them into the world and put them in front of an audience. I'm very excited about this current piece, though, so it's quite unlikely that will happen to this one.

RG: How does this piece fit into your overall output as a composer?

AM: Like I mentioned earlier, the instrumentation itself is forcing me into new harmonic and acoustic territory, so that alone is kind of thrilling. Also, I have a sort of devious streak to my personality and I often like to subvert a strict process or structure, or introduce an element of imperfection. In this piece I think the devious "streak" will take up most of the canvas.

Chris Burns

Russell Greenberg: What are / were some of the inspirations for "Close Quarters"?

Chris Burns: The most direct inspiration for "Close Quarters" was Yarn/Wire's visit to Milwaukee in 2011 as part of the Unruly Music festival. It was a genuine pleasure working with you to produce a pair of concerts, and it was a great opportunity to experience your musicianship "up close." I almost always compose with specific musicians in mind - "how will that sound when Laura and Ning play it?" and "how can Russell and Ian make that work?" are the kinds of questions that get me excited about composing. In hindsight, it's no surprise that ideas started flowing after your trip. Another key inspiration was Laura and Ning's performances of four-hands piano music by Alex Mincek and David Bithell. That got me thinking about the idea of shared instruments more generally - what if four people played a single piano simultaneously, or a single vibraphone? That notion became the kernel of "Close Quarters" - and from there the fire was lit.

RG: Can you describe your process in writing "Close Quarters"?

CB: The idea of shared instruments led quickly to a list of various possible combinations of musicians with vibraphone and piano - piano six-hands, piano four-hands with two musicians playing in the interior of the instrument, vibraphone eight-hands, and so on. The notion of moving from instrument to instrument led to the idea of a multi-movement piece (to simply the logistics of getting around the stage) and so I made an initial list of ideas for movements - textures, gestures, types of performance with the shared instruments - and made rough sketches of a few. After that it became a process of refinement and revision - each new movement I wrote taught me more about the piece as a whole, and triggered revisions to the movements already written as well as changes to the concepts for the movements left to write.

RG: What did you find particularly (intriguing, challenging, difficult, inspiring) about writing for our group in particular?

CB: One of the major challenges with the composition was finding a sequence for the nine movements that was both intellectually satisfying (the finished result makes lots of gestural, material, and harmonic connections across different movements, and investigates various kinds of symmetry over the course of the work) and dramatically and emotionally compelling (which is harder to explain or describe, but you know it when you hear it). My sketches must contain at least a dozen different proposals before I was finally able to dial in the right flow from movement to movement, and to compose and revise to make it all work. One of the most satisfying elements of composing the piece was knowing that Yarn/Wire would be able to perform any tricky unison rhythm, chunky chord, or unusual color I might want to write! It's a wonderful feeling of security for a composer, especially as I was trying out the choreographic complexities of shared instruments and inside-the-piano performance for the first time.

RG: What made you agree to write for the group?

CB: We all went out for beer after the concert, and the next thing I knew.... More seriously, I'd been hoping to make something for the group for a long time!

RG: What do you hope people will come away with after hearing "Close Quarters"?

CB: There's no "correct way" to hear "Close Quarters" - my intention is to make music that's rich with possible interpretations, so that each listener can follow the elements or aspects that they find most interesting. Hopefully that also makes a work that rewards repeated listening and experience, so that both musicians and audience can keep finding new things!

RG: How does "Close Quarters" fit into your overall output as a composer?

CB: "Close Quarters" builds on the personal approaches to writing for piano and vibraphone that I've developed in previous projects such as "Windwork" and "Trifold". And in many ways it is a sequel to an earlier duet for piano and percussion, "Xerox Book", which is also in nine short movements, though the specific structures and materials are quite different. Looking forward, "Close Quarters" opens up some new approaches to instrumental technique and performance choreography (as the musicians intertwine, entangle, and find ways to share instruments). Those ideas are already continuing and developing in new projects, and I'm excited to find out where they may lead.

Elizabeth Adams

Elizabeth Adams: Well, foremost in my mind’s ear is the growing body of memorable works Yarn/Wire has commissioned in the last few years -- especially from the Wet Ink composers on Tone Builders, and Nathan Davis’ recent piece. Also jangling around in my ear is Elizabeth Hoffman’s percussion writing for TimeTable, and her other work with Matt Gold. Then there’s the music theater of Mark Enslin, Rick Burkhardt, and Georges Aperghis. I haven’t written for the piano since 2005 and I’m trying to figure out what to do with my affinity for lush, frenchy chords. I learned a lot about piano acoustics from a tiny passage of a recording of Alvin Curran’s Inner Cities played by Daan Vandewalle. And most recently I’ve been inspired by the work of Gayle Young, who’s been presenting her instruments and pieces here at Xenharmonic Praxis Summer Camp.

RG: Can you describe your process in writing this new piece?

EA: I veer between sonic concerns and conceptual concerns and trying to pull them closer together. With percussion, it’s hard to commit to instrumentation and then use its constraints the way I would with a violin. The perpetual percussion temptation is to add another instrument every time you need a new sound, but of course percussionists and your own inherited sense of aesthetic economy advise against that. Since working with Elizabeth Hoffman I’ve been trying to get a new acoustic idea from inside an old idea, in a kind of Horton Hears A Who scenario.

RG: What did you find particularly (intriguing, challenging, difficult, inspiring) about writing for our group in particular?

EA: A sonic challenge has been how to harness more indeterminate pitch so that it confounds the ubiquitous tuning of the piano. How do I construct sounds that grow out of rapidly decaying sounds? When writing for the piano and pitched percussion, it’s hard to keep pitch and rhythm from having too much parametric weight. How can I deepen the social dramaturgy of recombining pairs of performers?

RG: What do you hope people will come away with after hearing this piece?

EA: I have these nagging, overblown criteria and interests I’m trying to get this piece to serve, but what success would even look like still requires formulation: I want music to have consequences. I want it to have more and different purposes than it already has. I want relations to seem more important than components in this piece, and I want what one player does or plays to appear to depend on what or how another player plays. I want this piece to dramatize different kinds of agency and listening, and I hope an audience member leaves thinking their own new thoughts about agency and listening, with some new sounds and images in their mind’s ear to help them remember while they think, remaining or becoming at least a little confused.